Kon Tiki Free Download

Kon-Tiki, 1947 The Kon-Tiki expedition was a 1947 journey by across the Pacific Ocean from South America to the Polynesian islands, led by Norwegian explorer and writer. The raft was named Kon-Tiki after the sun god, for whom 'Kon-Tiki' was said to be an old name. Is also the name of Heyerdahl's book; the -winning chronicling his adventures; and the nominated for the. Heyerdahl believed that people from South America could have settled Polynesia in times.

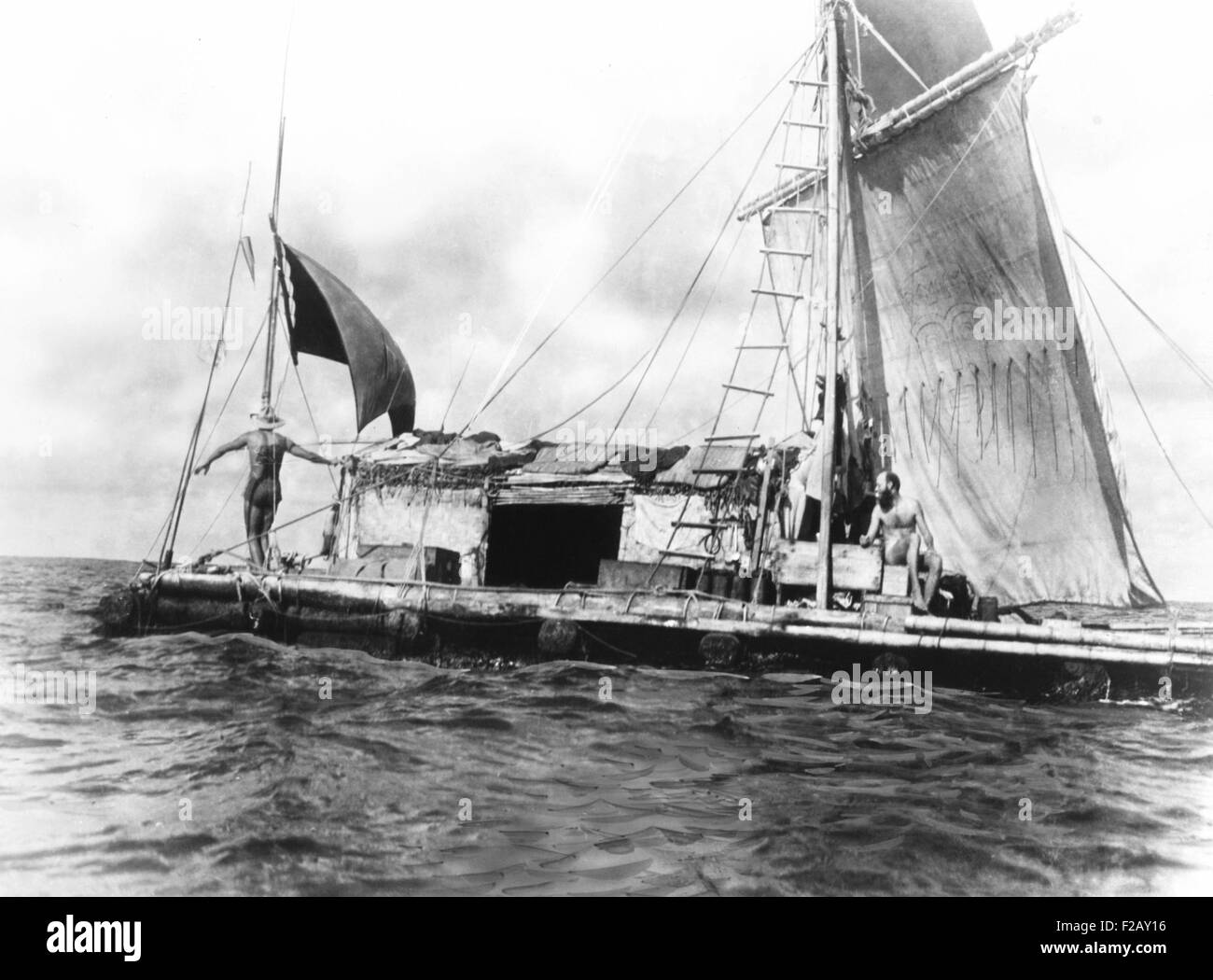

His aim in mounting the Kon-Tiki expedition was to show, by using only the materials and technologies available to those people at the time, that there were no technical reasons to prevent them from having done so. Although the expedition carried some modern equipment, such as a radio, watches, charts, and metal knives, Heyerdahl argued they were incidental to the purpose of proving that the raft itself could make the journey. The Kon-Tiki expedition was funded by private loans, along with donations of equipment from the. Heyerdahl and a small team went to, where, with the help of dockyard facilities provided by the Peruvian authorities, they constructed the raft out of logs and other native materials in an indigenous style as recorded in illustrations by Spanish. The trip began on April 28, 1947. Heyerdahl and five companions sailed the raft for 101 days over 6,900 km (4,300 miles) across the Pacific Ocean before smashing into a at in the on August 7, 1947.

The crew made successful landfall and all returned safely. Thor Heyerdahl's book about his experience became a bestseller. It was published in Norwegian in 1948 as The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas, later reprinted as Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific in a Raft. It appeared with great success in English in 1950, also in many other languages. A documentary about the expedition, also called Kon-Tiki, was produced from a write-up and expansion of the crew's filmstrip notes and won an in 1951.

It was directed by and edited. The voyage was also chronicled in the documentary TV-series The Kon-Tiki Man: The Life and Adventures of Thor Heyerdahl, directed by Bengt Jonson.

The original Kon-Tiki raft is now on display in the at in. Contents. Crew Kon-Tiki had a six-man crew, all of whom were Norwegian except for Bengt Danielsson, a Swede. (1914–2002) was the expedition leader. He was also the author of the book of the expedition and the narrator of the story. Heyerdahl had studied the ancient people of South America and Polynesia and believed that there was a link between the two.

(1914–1972) was the navigator and artist. He painted the large Kon-Tiki figure on the raft's sail. His children's book Kon-Tiki and I appeared in Norwegian in 1949 and has since been published in more than 15 languages. (1921–1997) took on the role of steward, in charge of supplies and daily rations. Danielsson was a Swedish sociologist interested in.

He also served as translator, as he was the only member of the crew who spoke Spanish. He was also a voracious reader; his box aboard the raft contained many books. (1917–2009) was a radio expert, decorated by the British in World War II for actions in the that stalled what were believed to be Germany's plans to develop an. Haugland was the last surviving crew member; he died on Christmas Day, 2009 at the age of 92. (1918–1964) was also in charge of radio transmissions. He gained radio experience while hiding behind German lines during WWII, spying on the German battleship.

His secret radio transmissions eventually helped guide in Allied bombers to sink the ship. (1910–1986) was an engineer whose area of expertise was in technical measurements. He was the first to join Heyerdahl for the trip. He collected and recorded all sorts of data on the voyage. Much of what he recorded, such as weather data, was sent back to various people, since this area of the ocean was largely unstudied. The expedition also carried a pet named Lorita. Construction The main body of the float was composed of nine tree trunks up to 14 m (45 ft) long, 60 cm (2 ft) in diameter, lashed together with 30 mm ( 1 1⁄ 4 in) ropes.

Cross-pieces of balsa logs 5.5 m (18 ft) long and 30 cm (1 ft) in diameter were lashed across the logs at 91 cm (3 ft) intervals to give lateral support. Splashboards clad the bow, and lengths of pine 25 mm (1 in) thick and 60 cm (2 ft) wide were wedged between the balsa logs and used as. The main mast was made of lengths of mangrove wood lashed together to form an A-frame 8.8 m (29 ft) high. Behind the main-mast was a cabin of plaited bamboo 4.3 m (14 ft) long and 2.4 m (8 ft) wide was built about 1.2–1.5 m (4–5 ft) high, and roofed with banana leaf thatch. At the stern was a 5.8 m (19 ft) long steering oar of mangrove wood, with a blade of fir. The main sail was 4.6 by 5.5 m (15 by 18 ft) on a yard of bamboo stems lashed together.

Photographs also show a top-sail above the main sail, and also a mizzen-sail, mounted at the stern. The raft was partially decked in split bamboo. The main spars were a laminate of wood and reeds and Heyerdahl tested more than twenty different composites before settling on one that proved an effective compromise between bulk and torsional rigidity. No metal was used in the construction. Supplies Kon-Tiki carried 1,040 litres (275 US gal) of drinking water in 56 water cans, as well as a number of sealed bamboo rods.

The purpose stated by Heyerdahl for carrying modern and ancient containers was to test the effectiveness of ancient water storage. For food Kon-Tiki carried 200, and other assorted fruit and roots. The provided, tinned food and survival equipment. In return, the Kon-Tiki explorers reported on the quality and utility of the provisions. They also caught plentiful numbers of fish, particularly, ', and. Communications.

National NC-173 radio receiver used by the expedition. The expedition carried an station with the call sign of LI2B operated by former radio operators Knut Haugland and Torstein Raaby. Haugland and Raaby maintained regular communication with a number of American, Canadian, and South American stations that relayed Kon Tiki's status to the Norwegian Embassy in Washington, D.C. On August 5, Haugland made contact with a station in Oslo, Norway, 16,000 kilometres (10,000 mi) away. Kon Tiki's transmitters were powered by batteries and a hand-cranked generator and operated on the, and. Each unit was water resistant, used, and provided approximately 6 of output; the equivalent of a small.

Two British 3-16 MHz Mark II transmitters were also carried on board, as was a VHF transmitter for communicating with aircraft and a hand-cranked of the Gibson Girl type for 500 and 8280 kHz. The radio receiver used throughout the voyage, a NC-173, once required a thorough drying out after being soaked when landing in Raratonga. The crew once used a hand-cranked emergency transmitter to send out an 'all well, all well' message 'just in time to head off a massive rescue attempt'. The call sign LI2B was used by Heyerdahl again in 1969–70, when he built a papyrus reed raft and sailed from Morocco to Barbados in an attempt to show a possible link between the civilization of ancient Egypt and the New World. The voyage Kon-Tiki left, on the afternoon of April 28, 1947. To avoid coastal traffic it was initially towed 80 km (50 mi) out by the Fleet Tug Guardian Rios of the, then sailed roughly west carried along on the.

The crew's first sight of land was the atoll of on July 30. On August 4, the 97th day after departure, Kon-Tiki reached the Angatau atoll.

The crew made brief contact with the inhabitants of, but were unable to land safely. Calculations made by Heyerdahl before the trip had indicated that 97 days was the minimum amount of time required to reach the Tuamotu islands, so the encounter with Angatau showed that they had made good time.

On August 7, the voyage came to an end when the raft struck a reef and was eventually beached on an uninhabited islet off in the group. The team had travelled a distance of around 6,980 km (4,340 mi; 3,770 nmi) in 101 days, at an average speed of 1.5 knots (2.8 km/h; 1.7 mph). After spending a number of days alone on the tiny islet, the crew was greeted by men from a village on a nearby island who arrived in canoes, having seen washed-up flotsam from the raft. The crew were taken back to the native village, where they were feted with traditional dances and other festivities. Finally the crew were taken off Raroia to by the French schooner Tamara, with the salvaged Kon-Tiki in tow.

Anthropology. A Heyerdahl believed that the original inhabitants of were migrants from Peru. He argued that the monumental statues known as resembled sculptures more typical of pre-Columbian Peru than any Polynesian designs.

He believed that the Easter Island myth of a power struggle between two peoples called the and was a memory of conflicts between the original inhabitants of the island and a later wave of Native Americans from the Northwest coast, eventually leading to the annihilation of the Hanau epe and the destruction of the island's culture and once-prosperous economy. Most historians consider that the Polynesians from the west were the original inhabitants and that the story of the Hanau epe is either pure myth, or a memory of internal tribal or class conflicts. In 2011 Professor Erik Thorsby of the presented DNA evidence to the which whilst agreeing with the west origin also identified a distinctive but smaller genetic contribution from South America. This result was questioned in 2012 because of the possibility of contamination by South Americans after European contact with the islands.

In 2014 further work by a team including Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas (from the Natural History Museum of Denmark) analysed the genomes of 27 native people and found that their DNA was on average 76 percent Polynesian, 8 percent Native American and 16 percent European. Analysis showed that 'although the European lineage could be explained by contact with white Europeans after the island was 'discovered' in 1722 by Dutch sailors, the South American component was much older, dating to between about 1280 and 1495, soon after the island was first colonised by Polynesians in around 1200.' Later recreations of Kon-Tiki Seven Little Sisters In 1954 sailed alone on a raft Seven Little Sisters from to, successfully completing the journey. He sailed 10,800 km (6,700 mi), which was 3,500 km (2,200 mi) farther than Kon-Tiki. In a second great voyage ten years later, he rafted 12,001 km (7,457 mi) from South America to Australia with a metal raft Age Unlimited.

Kantuta In 1955, the Czech explorer and adventurer attempted to recreate the Kon-Tiki expedition on a balsa raft called. His first expedition, Kantuta I, took place in 1955–1956 and led to failure. In 1959 Ingris built a new balsa raft, Kantuta II, and tried to repeat the previous expedition. The second expedition was a success.

Ingris was able to cross the Pacific Ocean on the balsa raft from Peru to Polynesia. Tahiti-Nui A French seafarer, committed himself in a project he had had for some years: he built a Polynesian raft in order to cross the eastern Pacific Ocean from to (contrary to 's crossing); the Tahiti-Nui left with a crew of five on November 8, 1956. When near the (Chile) in May 1957, the raft was in a very poor state and they asked for a towing, but it was damaged during the operation and had to be abandoned, but they could keep all the equipment aboard. Tahiti-Nui II A second Tahiti-Nui was built in; they left on April 13, 1958, towards, then towards the Marquesas, but they missed their target (after 4 months, it began to sink). His crew built a new smaller raft, the Tahiti Nui III, in the ocean out of the more buoyant parts of the Tahiti Nui II and were swept along towards where on August 30, the raft went aground and was wrecked at atoll. Eric de Bisschop was the only person who died in this accident. Tangaroa A Peruvian expedition led by crossed the Pacific Ocean in 1965 in 115 days in a raft named Tangaroa, of which 18 days were used by the crew to cross, the Tuamotu Archipielago, making Tangaroa the only raft that has managed to cross that dangerous archipelago of by its own means.

On November 18, 1965, the Tangaroa ended its journey on the island. Fakarava is where the Tangaroa is currently preserved. Las Balsas The 1973 expedition was the first (and so far only) multiple-raft crossing of the Pacific Ocean in recent history.

It is the longest-known raft voyage in history. The expedition was led by Spaniard, who, in 1970, led the expedition, only on that occasion with one raft and three companions.

Kon Tiki Free Download For Pc

The crossing was successful and, at the time, the longest raft voyage in history, until eclipsed in 1973 by Las Balsas. The purpose of the 1973 expedition was three-fold: (1) to prove that the success of 1970 was no accident, (2) to test different currents in the sea, which Alsar maintained ancient mariners knew as modern humans know road maps, and (3) to show that the original expeditions, directed perhaps toward trade or colonisation, may have consisted of small fleets of balsa rafts.

Tangaroa. October 28, 2007, at the. Thor Heyerdahl, Thor (1968). Rand McNally. Retrieved 5 April 2012. Heyerdahl, Thor (1984).

Rand McNally. Retrieved 5 April 2012. ^ Anonymous (December 1947). 'Kon-Tiki Communications – Well Done!' The: 69, 143–48., March 5, 2003., April 24, 2014. Thor Heyerdahl (7 May 2013).

Simon & Schuster. Retrieved 29 August 2013. September 23, 2011. Archived from on August 23, 2016.

Retrieved 2011-11-09. American Radio Relay League. Archived from on November 25, 2002. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

Thor Heyerdahl (1971). The Ra Expeditions (English ed.). New York: Doubleday and Company. Heyerdahl, Thor (1984). Rand McNally. Retrieved 5 April 2012. Heyderdahl, Thor.

Easter Island – The Mystery Solved. Random House New York 1989. Suggs, 'Kon-Tiki', in Rosemary G. Gillespie, D. Clague (eds), Encyclopedia of Islands, University of California Press, 2009, pp.

Long, 'Does 'Rapa Nui' Take Artistic License Too Far?' , Los Angeles Times, Friday August 26, 1994, p. John Flenley, Paul G. Bahn, The Enigmas of Easter Island: Island on the Edge, Oxford University Press, 2003, pp.

Fischer, Island at the End of the World: The Turbulent History of Easter Island, Reaktion Books, 2005, p. Richard Alleyne (17 Jun 2011). Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 17 Jun 2011.

Retrieved 2015-10-25. The Independent. Retrieved 2015-10-25. Evidence found of contact between Easter Islanders and South America.

Willis, William (1955). The Epic Voyage of the Seven Little Sisters: A 6700 Mile Voyage Alone Across the Pacific. London: Hutchinson. James Wharram Designs. James Wharram Designs. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

Tangaroa Crew. Azerbaijan International, Vol 14:4 (Winter 2006), p. Retrieved 2011-11-09.

Retrieved 2011-11-09. Retrieved 27 April 2013. Thor Heyerdahl (1948). The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas. Bibliography. Heyerdahl, Thor; Lyon, F.H. Aahat 2010 all episode online. (translator) (1950).

Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific by Raft. Rand McNally & Company, Chicago, Ill. Hesselberg, Erik (1950). Kon-Tiki and I: illustrations with text, begun on the Pacific on board the raft 'Kon-Tiki' and completed at 'Solbakken' in Borre. Allen & Unwin. Andersson, Axel (2010) A Hero for the Atomic Age: Thor Heyerdahl and the Kon-Tiki Expedition (Peter Lang) External links Media related to at Wikimedia Commons.

Azerbaijan International, Vol 14:4 (Winter 2006). Azerbaijan International, Vol 14:4 (Winter 2006). Librarything, 2007. personal.psu.edu.